This piece emerges from a series of reflective conversations between two educators thinking from different edges of childhood. Rachana is a trained early childhood educator and a recent mother, learning daily from the intimate, embodied experience of raising a young child. Vinay works as a systems practitioner in public education, engaging with questions of design, policy, and scale. What follows is not a set of answers or prescriptions, but a shared attempt to think aloud, about childhood, adulthood, and what “positive growth” might actually ask of us.

When we say a child should “grow positively,” we are usually saying far less, and demanding far more, than we realise.

Positive growth is not just a line on a chart or a list of milestones. It is the feeling of a child who knows: “There are people here for me. I am seen. I am safe enough to try, and also to fail.

It is also a question to adults: “What are you doing with your power in my life?”.

What does “positive growth” feel like?

Rachana reaches for an image when she tries to define it: a stream of water finding its path, or clay that will take a shape whether or not an adult is present. Her son will grow anyway; the question is not if he will grow, but how her presence bends that stream.

For her, positive growth is not about producing a particular kind of child, but about tending to the conditions: a child who is happy, held, allowed to explore, who is not being moulded through pressure or fear. She wants him to “get” certain qualities but is uncomfortable with pushing them into him. If he does not “achieve” them, she sees that as a signal to look at herself and her environment, not as a failure of the child.

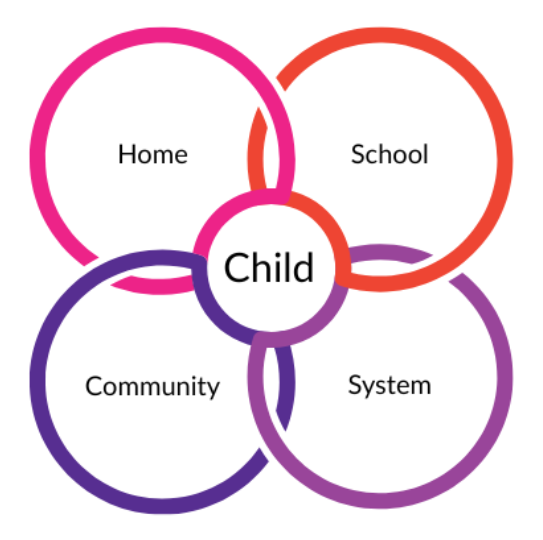

From the systems side, positive growth stretches across domains: physical, cognitive, social, emotional, all towards being prepared for the future of work, planet, and their own life. A well-fed, well-rested child is more likely to learn; a child held by loving adults in multiple circles, family, neighbourhood, school, has more places to stand in the world. But there is a clear refusal to reduce growth to marks or scores. If a child is not doing well on exams, the question is: have we failed to design assessments that can actually see this child, rather than declaring the child to be lacking?

Across both perspectives, what returns again and again is that positive growth is less about outcomes and more about experiences, being safe, being heard, being allowed to explore, and being met by adults who are attentive rather than anxious. It is not a finish line, but a texture of everyday life.

What both of us keep circling back to is simple and demanding: a growing child who is happy, nourished, safe, loved, and invited into the world as a person, not a project.

Ideal childhood or adult story?

When we talk about an “ideal childhood,” we often talk from the outside. We imagine the right school, the right activities, the right mix of nature and books and screen-free afternoons. But an “ideal childhood” is usually a story adults tell later, when childhood is over.

Rachana leans on an older language here, Tagore’s image of the child as a bud. The ideal, if it exists at all, lies not in how a child behaves, but in how the world behaves with the child: with care, time, trust, and the willingness to listen when the child calls. That is an ethical definition, not a behavioural one. Read this way, the question quietly turns toward adults: if the child is a bud, what kind of world are we creating around them, and what kind of adults are we choosing to be in that world?

From a system lens, any single definition of “ideal” quickly collapses. A child in a village in Uttarakhand and a child in an apartment in Bangalore live very different lives. Geography, caste, socio-economic class, language, religion, all shape what is possible, what is safe, what is available. A quiet, shy child in one setting is praised as “well-behaved”; in another, worried adults whisper, “Why is she like this?” Adults are extremely convenient in how they define a “good child”: healthy, but not too thin; active, but not disruptive; outspoken, but not disobedient.

So instead we must hold a smaller, more honest frame: if across these diverse worlds a child’s needs are met, if they feel safe, loved, and free enough to explore and form their own sense of self, then that is already precious, relevant, meaningful.

The work is not to chase an ideal childhood, but to keep asking whose comfort that ideal serves, the child’s, or the adults’?

Adulthood: power, responsibility, and the tired parent at 9 p.m.

As children, both of us thought adulthood was mainly freedom. Adults could decide, speak loudly, argue back, earn money, come home late. From the inside, adulthood looks very different. It is a dense web of responsibilities, expectations, and invisible labour, especially for parents and specifically more for mothers.

Rachana describes this phase as a continuous struggle: caring for a child, managing a household, meeting work expectations, carrying cultural norms. She laughs at her younger self’s assumption that adults are always happy; now she sees happiness as something that dips between stretches of duty and worry, and returns in moments, not phases.

From the systems side, adulthood is also shaped by consumerism and social scripts. Society quietly hands adults a checklist (and the very same template to children): career, marriage, progeny, home, adequate lifestyles. With each item comes pressure to provide, to appear successful, to “give the best” to your child, even if that “best” is defined more by markets than by children’s needs.

So what does this mean for positive growth? The shift both of us keep returning to is from power to responsibility. Power says: “I am the adult, I decide.” Responsibility asks: “Given that I have power, how do I use it so this child is not harmed by my ambition, my exhaustion, my unresolved fears?” That question does not make adulthood lighter; it makes it more honest.

Home, school, and the child in between

Rachana’s life is full of small, daily experiments as a mother. She notices how her son imitates her: if she is reading, he wanders toward books; if she is on her phone, he reaches for screens. She realises that “parenting” is less about controlling his behaviour and more about examining her own. When he lies, she wonders not just “Why is he lying?” but also “What has he seen from us? What does he think lying does for him right now?”

At school, the same child folds his mat neatly, follows routines, and does things he resists at home. His teacher points out that he seeks a lot of attention, either because he is getting too much of it, or too little. That single observation opens a line of introspection at home, and slowly, with small adjustments, his behaviour shifts.

For the system practitioner, this is exactly where school has a unique vantage point. A teacher sees a child among thirty others, watches how they share, withdraw, compete, or comfort. A parent sees the same child in the compressed intimacy of home, siblings, and cousins. Both views are partial; together, they can become a fuller picture, but only if there is trust and conversation between the adults, not silent judgement.

Mother and teacher share care, but their roles are not interchangeable. Being a mother does not automatically make someone a teacher for twenty children; being a teacher does not qualify someone to walk into a home and tell a family how to raise their child. Training matters, context matters, and so does humility in both roles.

When schools and homes pull in opposite directions, the child has to learn two incompatible scripts. When they are in dialogue, the child has a better chance of experiencing consistency, safety, and the freedom to explore, which are the key ingredients of positive growth.

Can schools be extensions of safe homes?

This question sits exactly at the intersection of hope and realism.

Rachana’s first move is to ask, “What do we even mean by safety?” If safety means a child never falls, never cries, never fights, then no space can be safe in that way—and trying to make it so may actually suffocate growth. Children need to climb, stumble, argue, make up, get muddy; without those experiences, resilience has nowhere to grow. For her, safety is about a child being able to be themselves, to express feelings without fear of ridicule or unjust punishment, and to know that when something goes wrong, there is an adult who will respond with care rather than just control.

From the systems side, the picture widens painfully. In some schools, there are mid-day meals, caring teachers, play spaces, and time for friendships; in others, there are single teachers handling multiple grades, broken toilets, long walks to school, and classrooms where fear is the main behaviour management strategy. It is hard to talk about “safe, home-like schools” in places where basic infrastructure and teacher support is missing.

And yet, there are classrooms—even in under-resourced settings—where children feel a profound sense of belonging because a teacher has chosen to stand differently in that room. There are also policy moves toward strengthening early childhood care and education that could, if supported well, create more such spaces.

So the answer we live with is layered: schools can be extensions of safe homes; they should aspire to be; but whether they are, right now, depends on a fragile mix of system design, resources, and the everyday choices of adults who are themselves overburdened.

Love, design, and the unfinished work of childhood

Underneath all these questions runs one more: does love automatically translate into the capacity to care well? For parents, for teachers, for policymakers, the uncomfortable answer is no. Love without reflection can become control, or overprotection, or a projection of one’s own fears and ambitions onto children.

What helps is not a perfect theory, but a posture: staying curious about the child, and equally curious about oneself as an adult in that child’s world. Watching how culture shows up in bedtime stories and school assemblies. Noticing when textbooks erase realities, when rituals comfort, and when they exclude. Tracking how quickly “for your own good” can silence a child’s voice.

Neither of us has a neat conclusion to offer. Childhood today is entangled with nuclear families, fragile support systems, addictive technology, and shifting gender roles. Systems are trying to catch up; adults are trying not to drown.

What feels worth holding on to is this: a child is not a blank slate or a vessel to be filled, but a person already becoming, already shaping the kind of adult they will be, even as adults shape them. Positive growth, then, is not a destination but a shared practice of adults pausing, looking again, and choosing, as often as they can, to see the child not as an extension of themselves, but as a human in their own right, standing at the centre of many overlapping worlds.

About the Author

Rachana Mishra

Rachana is from a small hilly village situated in Uttarakhand and has been living in Bangalore for the last 9 years. After doing her MA in education from Azim Premji University she worked as a research assistant in the university itself and afterwards started exploring different areas of education like education for differently abled people, alternative education via doing volunteer work and teaching.

She loves to read, cook and observe children‘s world.

Rachana is currently on a break from her professional journey because of her personal commitment towards her child.

Vinay R Sanjivi

Vinay is a systems leader and strategist, currently Head of Programs at ShikshaLokam, a nonprofit focused on strengthening leadership in India’s public education system. He designs and drives large-scale education programmes with governments and civil society, blending ecosystem thinking with on-ground insights. Previously, he led capacity-building initiatives for Andhra Pradesh’s residential schools and worked at Goldman Sachs as a Senior Finance Analyst. A Teach For India Fellow and policy consultant, Vinay holds a Master’s in Education from Azim Premji University. He is committed to building ecosystems where leadership is shared and every child can thrive.